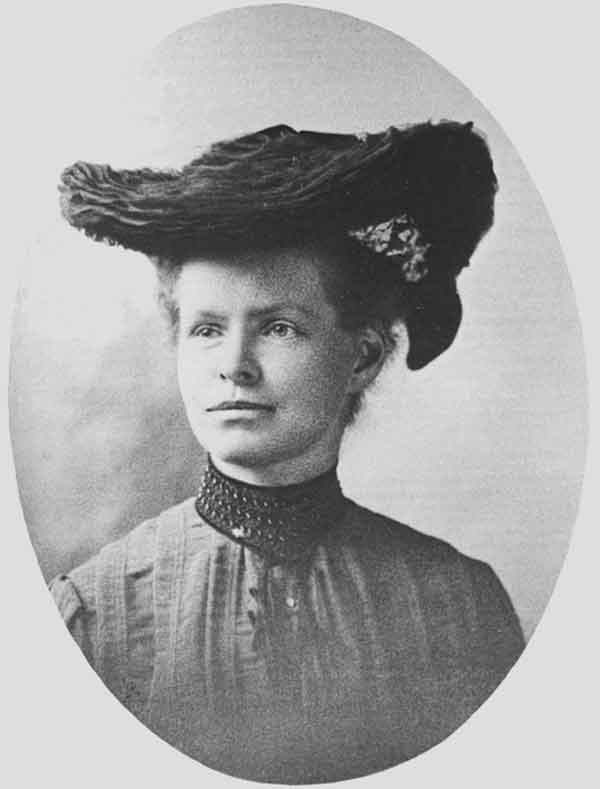

My hero du jour was one of the first biologists to notice this difference in the chromosomes; she was also a pioneer of women in her field and a somewhat controversial character, as posthumously it was difficult for her to hang on to her credits for the research work she did. Anyway, rocking her XX chromosomes like no other (and another spiffing hat), I give you...

Nettie Stevens (1861-1901)

Nettie Maria Stevens was born into a working-class Vermont family in 1861. Nettie, like so many of the women I’ve written about, was raised during a time when women's educational opportunities were limited to say the least. However, she was a promising student with a gift for science and mathematics, consistently scoring the highest in her classes. She attended college in Massachusetts, and spent the next ten years teaching, saving money from her wages so that she could fulfill her dreams of going to university, there certainly wasn’t any grants or student loans in those days!

In 1896, at the age of 35, Nettie attended Leland Stanford University, graduating with a masters’ in biology. After Stanford, she carried on her graduate work at Bryn Mawr College in Philadelphia. In 1903, Stevens was awarded her PhD, and was subsequently given an assistantship by the Carnegie Institute, after glowing recommendations from the president of Bryn Mawr.

During her research at Bryn Mawr and the Carnegie Institute Nettie discovered that in some species chromosomes are different among the sexes, mainly through her observations and research of insects (mainly mealworms). Investigating the mealworms, she found female cells contained 20 chromosomes, but male cells contained 19 large chromosomes and one very small one. She showed that the X body paired with a 20th, much smaller, chromosome in meiosis. She proposed that these two chromosomes be called X and Y, and explained that females contained two X chromosomes. The discovery was the first time that differences of chromosomes could be linked to an observable difference in physical. Nettie did experiments on a range of insects to determine this and prove her theories, and deduced the chromosomal basis of sex depended on the presence or absence of the Y chromosome.

As Nettie's scientific reputation grew, Bryn Mawr established a professorship for her, but alas she was not to take it. Nettie developed breast cancer and died in 1901, aged only 51. Following her death, her old head of department Thomas Hunt Morgan wrote an extensive, if somewhat dismissive, obituary for the journal Science, implying that she was more of a technician than a scientist, and some believe her position in the field of genetics has largely been ignored because the credit for the discovery of X and Y chromosomes is instead generally given to Morgan and his predecessor Edmund B. Wilson, who both received the Nobel prize for the discovery. But later manuscripts reveal that it was Nettie who discovered the two XXs. Although the history books may miss Nettie’s credit out, she is not to be forgotten, as without her attention to detail, the discovery may not have been made. She published more than 38 papers from 1901 to her death, in cytology and experimental physiology, and was one of the first American women to be recognized for her contribution to science. Proving that sometimes two Xs are better than one.

No comments:

Post a Comment