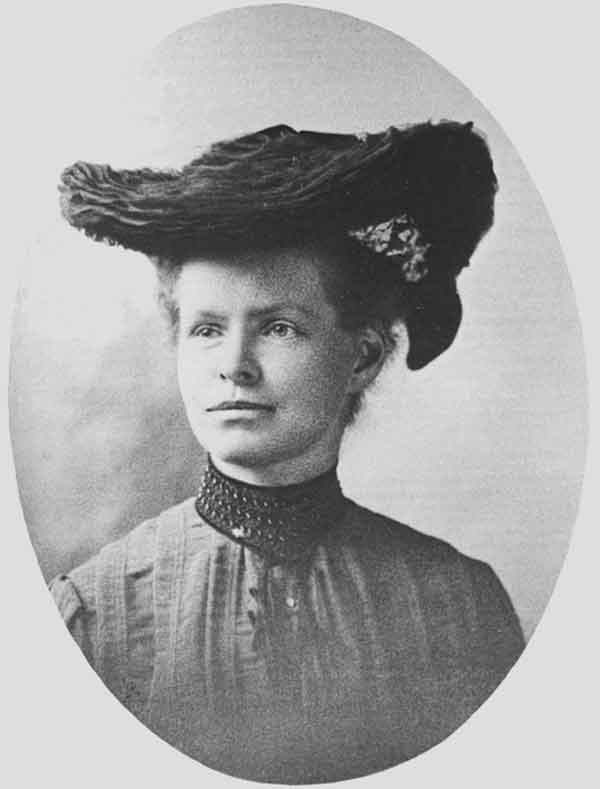

Elizabeth Blackwell (1821-1910)

But Bristol has always been beset by social unrest, and then was no different to now, with an unstable economy and riots brewing in the streets. Samuel Blackwell decided to move his whole family to the more flourishing America when Elizabeth was 11. Here the family continued their liberal ways, becoming committed abolitionists and champions of social reform. However, Samuel died only five years later, leaving behind debts and no business to speak of after his refinery burnt down.

Being proactive, Elizabeth and her older sisters opened a school to help the family out of their financial woes. Elizabeth taught in the school and once it became established she also started taking on private pupils. The school closed in 1842 as so she began to work more on other pursuits, such as becoming involved in political campaigns, writing about women’s rights, studying the arts and working to highlight the horrors of slavery.

When Elizabeth was 24 she got the inspiration to study medicine. Her friend was dying of a gynaecological cancer, and stressed that what made her situation all the worse was being treated by a ‘rough’ male medic. She urged her intelligent friend to train to be a doctor. The ideal appealed to Elizabeth, intellectually, and also because she believed she could use her compassion to help others, especially women. She also liked the idea of having a career that would help her live independently, without having to marry. Never one to shy away from a challenge, Elizabeth went about finding ways to fulfill her new ambition, even though no woman had trained in the field before.

Her first obstacle was money. She would need to raise $3,000 in order to pay for medical school tuition. She embarked on a series of teaching jobs while all the time independently teaching herself all she could from medical books and journals. She moved to Philadelphia in search of more opportunity. Here she took private anatomy lessons and tried to apply to medical schools, but was met with rejection everywhere. Her tutors suggested trying abroad, and even disguising herself as a man to get a foot in the door!

In 1947 she was finally accepted to Geneva Medical College in upstate New York, though her entry was just a jeering social experiment on the part of the college. It was not an easy time for Elizabeth; she was treated as an oddity, and met resistance throughout her studies. She had to fight to be allowed to attend the reproductive anatomy class for the tutor thought it might warp her ‘delicate female mind’, and the male students did everything they could to make her leave. Elizabeth kept her head down and pushed on through, rejecting taunts and scorn as well as suitors and male advances, instead completing most of her studies in isolation. She made it through and graduated in 1849, the first women in the United States to ever gain a medical degree.

It wasn’t easy getting work, even voluntary, and many male doctors refused to work alongside her and so she headed back to England, and then on to Paris, where after much more discrimination for her gender, she finally got to train to be an obstetrician. Elizabeth headed back to New York, finally fulfilling her dream of having her own private practice, and then clinic.

The New York Dispensary for Poor Women and Children was opened in 1853, and then the New York Infirmary for Indigent Women and Children in 1857. That same year, she became the first woman listed on the British Medical Register during a time when she was lecturing there.

In the late 1860s, Elizabeth also opened a medical school for women in New York – The Women’s Medical College of the New York Infirmary. Here Elizabeth put a focus on the importance of hygiene in the curriculum, something she had observed the importance of over her years of practice.

Elizabeth settled back in England for the remainder of her career. She set up a private practice in London and served as a lecturer at the London School of Medicine for Women. She finally retired in 1877, but continued to stay active, writing books and travelling, until a fall left her severely disabled at the age of 86. She died three years later in 1910. Her legacy was a doorway that let many women enter the medical profession as well as being an inspiration to those that did. Elizabeth, you did Bristol proud.